[:es]

From ‘covidiots’ to ‘quarantine and chill’, the pandemic has led to many terms that help people laugh and commiserate.

Many of the newly popular terms relate to the socially distanced nature of human contact these days, such as ‘virtual happy hour’, ‘covideo party’ and ‘quarantine and chill’. Many use ‘corona’ as a prefix, whether Polish speakers convert ‘coronavirus’ into a verb or English speakers wonder how ‘coronababies’ (the children born or conceived during the pandemic) will fare. And, of course, there are abbreviations, like the ubiquitous ‘WFH’ and the life-saving ‘PPE’.

Old words in a new light

Like everyone else, lexicologists are scrambling to keep up with the changes the pandemic has wrought. According to Fiona McPherson, the senior editor of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), back in December ‘coronavirus’ appeared only 0.03 times per million tokens (tokens are the smallest units of language collected and tracked in the OED corpus). The term ‘Covid-19’ was only coined in February, when the WHO announced the official name of the virus. But in April, the figures for both ‘Covid-19’ and ‘coronavirus’ had skyrocketed to about 1,750 per million tokens (suggesting that the two terms are now being used at roughly the same frequency).

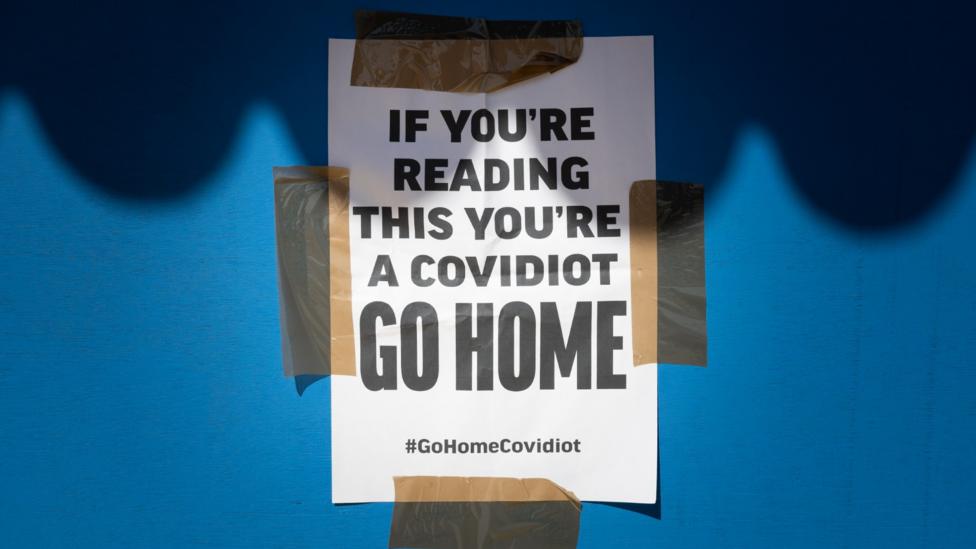

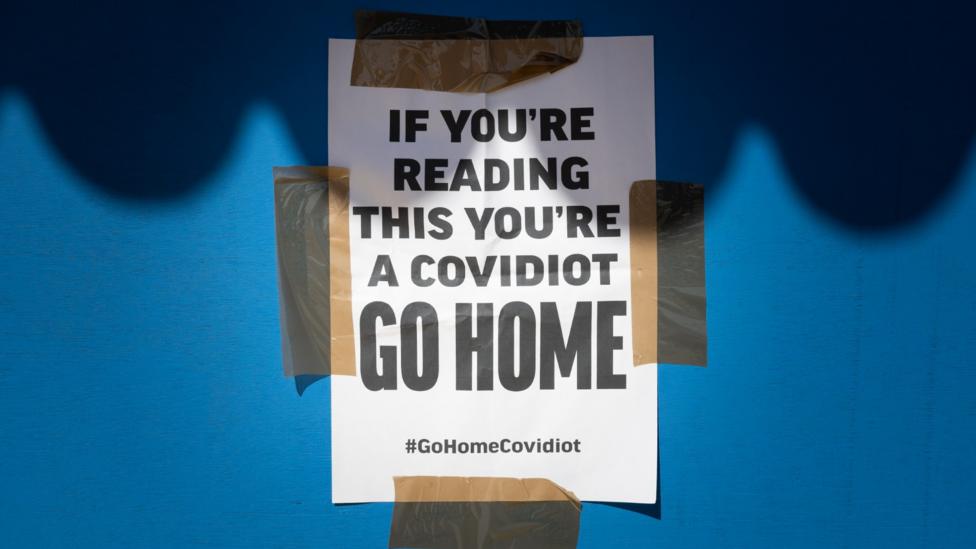

Innovative signs: In the UK, ‘covidiots’ is being used to described those ignoring social distancing rules

“Although a lot of the words we’re using just now and a lot of the terminology is actually older, a lot of it seems fairly new. ‘Coronavirus’ itself goes back to the 1960s,” she points out.

What McPherson calls the “nuancing of already existing words” can in some cases be subtly harmful. War metaphors invoking ‘battles’ and ‘front-lines’ are being widely applied to the pandemic, yet thinking only in terms of a wartime emergency can detract from longer-term structural changes needed. This has given rise to the project #ReframeCovid, in which linguists collect crowdsourced examples of alternatives to war language.

Inés Olza, a linguist at the University of Navarra in Spain, says she started the project spontaneously on Twitter. She understands the temptation to invoke war metaphors, especially at the start of the pandemic when they were necessary to build unity and mobilise swiftly. But “a sustained use of that metaphor and abuse of it, and the lack of alternative frames, might generate anxiety and might distort things about the pandemic”, she believes.

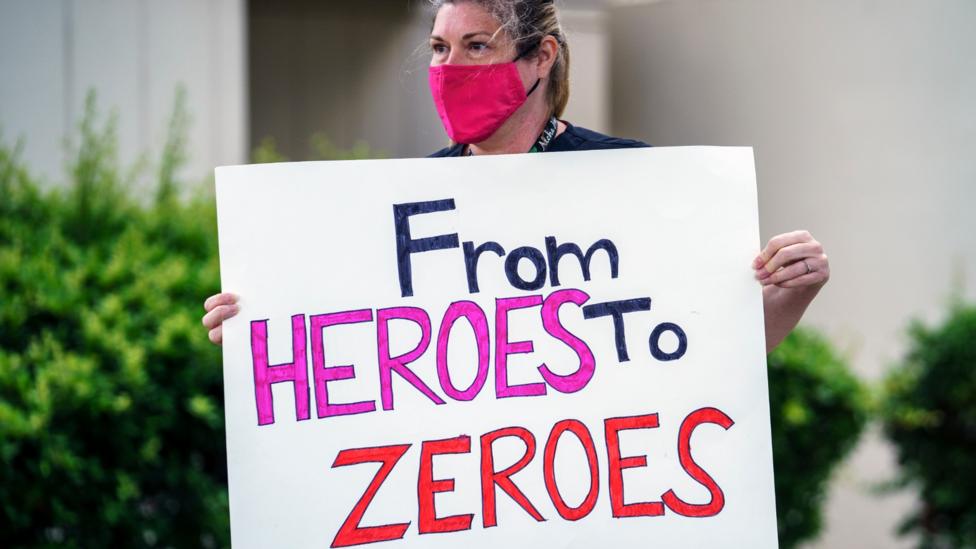

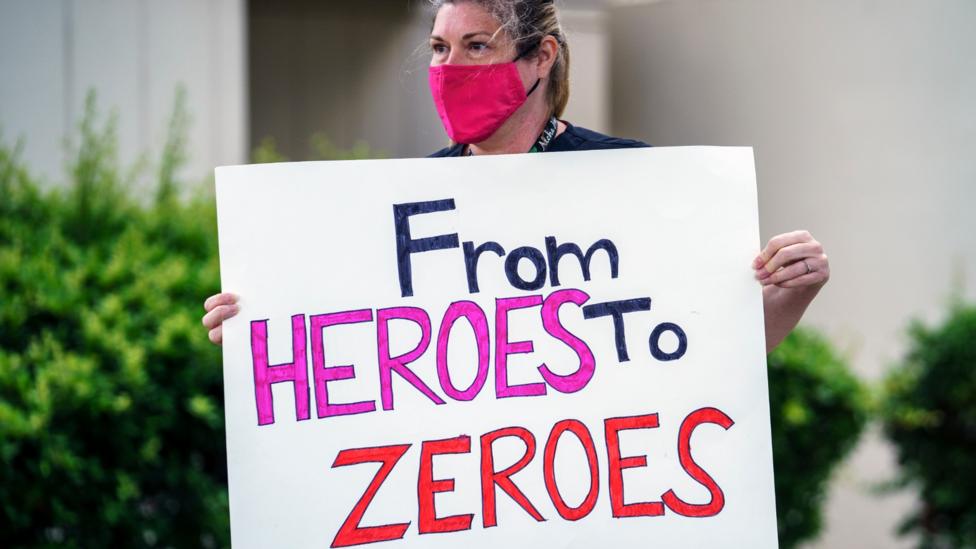

As well, terms such as ‘natural disaster’ and ‘perfect storm’ can create the impression that the pandemic was inevitable and unavoidable, neglecting the political, economic and environmental contexts that make certain people more exposed. Some healthcare workers have expressed their frustration at being called ‘heroes’, rather than seen as complex, frightened individuals doing a job, who need protective equipment and policy rather than relying on their own sacrifices.

In some cases the language being used isn’t appreciated: this US healthcare worker is protesting against a lack of PPE

Why humour helps

Overall, there’s a wealth of linguistic creativity that hasn’t yet entered the dictionary, but reflects the role of novel language as a coping mechanism. These innovative usages, Lawson says, “allow us to name whatever it is that’s going on in the world. And once you can name the practices, the events, the social conditions around a particular event, it just gives people a shared vocabulary that they can all use as a bit of a shorthand. I think ultimately if you can name it, you can talk about it; and if you can talk about it, then it can help people cope and get a handle on really difficult situations”.

Writer Karen Russell has found the newly ubiquitous term ‘flatten the curve’ to be reassuring – a reminder of the importance of both individual and collective action, which “alchemizes fear into action”. And both the practice and the terminology of ‘caremongering’, used for instance in Canadian and Indian English, allow for an alternative to scaremongering.

Beyond earnest words like these, a kind of slightly anxious humour is central to many of the ‘coronacoinages’. The German ‘coronaspeck’, like the English ‘Covid 19’, playfully refers to stress eating amid stay-at-home orders. The Spanish ‘covidiota’ and ‘coronaburro’ (a play on ‘burro’, the word for donkey) poke fun at the people disregarding public health advice. ‘Doomscrolling’ describes the hypnotic state of endlessly reading grim internet news. Lawson’s favourite, ‘Blursday’, captures the weakening sense of time when so many days bleed into each other.

I don’t think that by having a little bit of light in the dark, people are making light of the situation – Fiona McPherson

Some of these emojis and terms might seem flippant, but “I don’t think that by having a little bit of light in the dark, people are making light of the situation”, says McPherson. Lawson agrees: “If you can laugh at them, it makes things more manageable almost, and just helps with people’s psychological health more than anything else.”

Linguists believe that many of the terms currently in vogue won’t endure. The ones with a stronger chance of sticking around post-pandemic are those that describe lasting behavioural changes, such as ‘zoombombing’, which is influenced by ‘photobombing’ and describes the practice of invading someone else’s video call. McPherson reckons that ‘zoombombing’ could become a generic term (like ‘hoovering’ up a mess) even if the company Zoom loses its market dominance.

Ingenuity with vocabulary can also communicate that the current hardships, like many of the coronacoinages, won’t last forever. Olza has taken to referring to the tasks on her ‘corona-agenda’, which can be a subtle way of asking for people’s patience with her temporarily disrupted schedule. Eventually “I will get my usual agenda back,” she says hopefully.

Until then, bring on the quarantinis.

Why we’ve created new language for coronavirus By Christine Ro

[:en]

From ‘covidiots’ to ‘quarantine and chill’, the pandemic has led to many terms that help people laugh and commiserate.

Many of the newly popular terms relate to the socially distanced nature of human contact these days, such as ‘virtual happy hour’, ‘covideo party’ and ‘quarantine and chill’. Many use ‘corona’ as a prefix, whether Polish speakers convert ‘coronavirus’ into a verb or English speakers wonder how ‘coronababies’ (the children born or conceived during the pandemic) will fare. And, of course, there are abbreviations, like the ubiquitous ‘WFH’ and the life-saving ‘PPE’.

Old words in a new light

Like everyone else, lexicologists are scrambling to keep up with the changes the pandemic has wrought. According to Fiona McPherson, the senior editor of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), back in December ‘coronavirus’ appeared only 0.03 times per million tokens (tokens are the smallest units of language collected and tracked in the OED corpus). The term ‘Covid-19’ was only coined in February, when the WHO announced the official name of the virus. But in April, the figures for both ‘Covid-19’ and ‘coronavirus’ had skyrocketed to about 1,750 per million tokens (suggesting that the two terms are now being used at roughly the same frequency).

Innovative signs: In the UK, ‘covidiots’ is being used to described those ignoring social distancing rules

“Although a lot of the words we’re using just now and a lot of the terminology is actually older, a lot of it seems fairly new. ‘Coronavirus’ itself goes back to the 1960s,” she points out.

What McPherson calls the “nuancing of already existing words” can in some cases be subtly harmful. War metaphors invoking ‘battles’ and ‘front-lines’ are being widely applied to the pandemic, yet thinking only in terms of a wartime emergency can detract from longer-term structural changes needed. This has given rise to the project #ReframeCovid, in which linguists collect crowdsourced examples of alternatives to war language.

Inés Olza, a linguist at the University of Navarra in Spain, says she started the project spontaneously on Twitter. She understands the temptation to invoke war metaphors, especially at the start of the pandemic when they were necessary to build unity and mobilise swiftly. But “a sustained use of that metaphor and abuse of it, and the lack of alternative frames, might generate anxiety and might distort things about the pandemic”, she believes.

As well, terms such as ‘natural disaster’ and ‘perfect storm’ can create the impression that the pandemic was inevitable and unavoidable, neglecting the political, economic and environmental contexts that make certain people more exposed. Some healthcare workers have expressed their frustration at being called ‘heroes’, rather than seen as complex, frightened individuals doing a job, who need protective equipment and policy rather than relying on their own sacrifices.

In some cases the language being used isn’t appreciated: this US healthcare worker is protesting against a lack of PPE

Why humour helps

Overall, there’s a wealth of linguistic creativity that hasn’t yet entered the dictionary, but reflects the role of novel language as a coping mechanism. These innovative usages, Lawson says, “allow us to name whatever it is that’s going on in the world. And once you can name the practices, the events, the social conditions around a particular event, it just gives people a shared vocabulary that they can all use as a bit of a shorthand. I think ultimately if you can name it, you can talk about it; and if you can talk about it, then it can help people cope and get a handle on really difficult situations”.

Writer Karen Russell has found the newly ubiquitous term ‘flatten the curve’ to be reassuring – a reminder of the importance of both individual and collective action, which “alchemizes fear into action”. And both the practice and the terminology of ‘caremongering’, used for instance in Canadian and Indian English, allow for an alternative to scaremongering.

Beyond earnest words like these, a kind of slightly anxious humour is central to many of the ‘coronacoinages’. The German ‘coronaspeck’, like the English ‘Covid 19’, playfully refers to stress eating amid stay-at-home orders. The Spanish ‘covidiota’ and ‘coronaburro’ (a play on ‘burro’, the word for donkey) poke fun at the people disregarding public health advice. ‘Doomscrolling’ describes the hypnotic state of endlessly reading grim internet news. Lawson’s favourite, ‘Blursday’, captures the weakening sense of time when so many days bleed into each other.

I don’t think that by having a little bit of light in the dark, people are making light of the situation – Fiona McPherson

Some of these emojis and terms might seem flippant, but “I don’t think that by having a little bit of light in the dark, people are making light of the situation”, says McPherson. Lawson agrees: “If you can laugh at them, it makes things more manageable almost, and just helps with people’s psychological health more than anything else.”

Linguists believe that many of the terms currently in vogue won’t endure. The ones with a stronger chance of sticking around post-pandemic are those that describe lasting behavioural changes, such as ‘zoombombing’, which is influenced by ‘photobombing’ and describes the practice of invading someone else’s video call. McPherson reckons that ‘zoombombing’ could become a generic term (like ‘hoovering’ up a mess) even if the company Zoom loses its market dominance.

Ingenuity with vocabulary can also communicate that the current hardships, like many of the coronacoinages, won’t last forever. Olza has taken to referring to the tasks on her ‘corona-agenda’, which can be a subtle way of asking for people’s patience with her temporarily disrupted schedule. Eventually “I will get my usual agenda back,” she says hopefully.

Until then, bring on the quarantinis.

Why we’ve created new language for coronavirus By Christine Ro

[:fr]

From ‘covidiots’ to ‘quarantine and chill’, the pandemic has led to many terms that help people laugh and commiserate.

Many of the newly popular terms relate to the socially distanced nature of human contact these days, such as ‘virtual happy hour’, ‘covideo party’ and ‘quarantine and chill’. Many use ‘corona’ as a prefix, whether Polish speakers convert ‘coronavirus’ into a verb or English speakers wonder how ‘coronababies’ (the children born or conceived during the pandemic) will fare. And, of course, there are abbreviations, like the ubiquitous ‘WFH’ and the life-saving ‘PPE’.

Old words in a new light

Like everyone else, lexicologists are scrambling to keep up with the changes the pandemic has wrought. According to Fiona McPherson, the senior editor of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), back in December ‘coronavirus’ appeared only 0.03 times per million tokens (tokens are the smallest units of language collected and tracked in the OED corpus). The term ‘Covid-19’ was only coined in February, when the WHO announced the official name of the virus. But in April, the figures for both ‘Covid-19’ and ‘coronavirus’ had skyrocketed to about 1,750 per million tokens (suggesting that the two terms are now being used at roughly the same frequency).

Innovative signs: In the UK, ‘covidiots’ is being used to described those ignoring social distancing rules

“Although a lot of the words we’re using just now and a lot of the terminology is actually older, a lot of it seems fairly new. ‘Coronavirus’ itself goes back to the 1960s,” she points out.

What McPherson calls the “nuancing of already existing words” can in some cases be subtly harmful. War metaphors invoking ‘battles’ and ‘front-lines’ are being widely applied to the pandemic, yet thinking only in terms of a wartime emergency can detract from longer-term structural changes needed. This has given rise to the project #ReframeCovid, in which linguists collect crowdsourced examples of alternatives to war language.

Inés Olza, a linguist at the University of Navarra in Spain, says she started the project spontaneously on Twitter. She understands the temptation to invoke war metaphors, especially at the start of the pandemic when they were necessary to build unity and mobilise swiftly. But “a sustained use of that metaphor and abuse of it, and the lack of alternative frames, might generate anxiety and might distort things about the pandemic”, she believes.

As well, terms such as ‘natural disaster’ and ‘perfect storm’ can create the impression that the pandemic was inevitable and unavoidable, neglecting the political, economic and environmental contexts that make certain people more exposed. Some healthcare workers have expressed their frustration at being called ‘heroes’, rather than seen as complex, frightened individuals doing a job, who need protective equipment and policy rather than relying on their own sacrifices.

In some cases the language being used isn’t appreciated: this US healthcare worker is protesting against a lack of PPE

Why humour helps

Overall, there’s a wealth of linguistic creativity that hasn’t yet entered the dictionary, but reflects the role of novel language as a coping mechanism. These innovative usages, Lawson says, “allow us to name whatever it is that’s going on in the world. And once you can name the practices, the events, the social conditions around a particular event, it just gives people a shared vocabulary that they can all use as a bit of a shorthand. I think ultimately if you can name it, you can talk about it; and if you can talk about it, then it can help people cope and get a handle on really difficult situations”.

Writer Karen Russell has found the newly ubiquitous term ‘flatten the curve’ to be reassuring – a reminder of the importance of both individual and collective action, which “alchemizes fear into action”. And both the practice and the terminology of ‘caremongering’, used for instance in Canadian and Indian English, allow for an alternative to scaremongering.

Beyond earnest words like these, a kind of slightly anxious humour is central to many of the ‘coronacoinages’. The German ‘coronaspeck’, like the English ‘Covid 19’, playfully refers to stress eating amid stay-at-home orders. The Spanish ‘covidiota’ and ‘coronaburro’ (a play on ‘burro’, the word for donkey) poke fun at the people disregarding public health advice. ‘Doomscrolling’ describes the hypnotic state of endlessly reading grim internet news. Lawson’s favourite, ‘Blursday’, captures the weakening sense of time when so many days bleed into each other.

I don’t think that by having a little bit of light in the dark, people are making light of the situation – Fiona McPherson

Some of these emojis and terms might seem flippant, but “I don’t think that by having a little bit of light in the dark, people are making light of the situation”, says McPherson. Lawson agrees: “If you can laugh at them, it makes things more manageable almost, and just helps with people’s psychological health more than anything else.”

Linguists believe that many of the terms currently in vogue won’t endure. The ones with a stronger chance of sticking around post-pandemic are those that describe lasting behavioural changes, such as ‘zoombombing’, which is influenced by ‘photobombing’ and describes the practice of invading someone else’s video call. McPherson reckons that ‘zoombombing’ could become a generic term (like ‘hoovering’ up a mess) even if the company Zoom loses its market dominance.

Ingenuity with vocabulary can also communicate that the current hardships, like many of the coronacoinages, won’t last forever. Olza has taken to referring to the tasks on her ‘corona-agenda’, which can be a subtle way of asking for people’s patience with her temporarily disrupted schedule. Eventually “I will get my usual agenda back,” she says hopefully.

Until then, bring on the quarantinis.

Why we’ve created new language for coronavirus By Christine Ro

[:]